Sir Adrian Boult would be pleased.

I thought it was worth finally posting on an issue close to my heart. A good friend and marvellous bass player recently suggested (and I'm not sure she was joking) that I was "belligerently antiphonal violins". I don't like to think that I am belligerently anything but in musical terms I suppose this is true.

I thought it was worth finally posting on an issue close to my heart. A good friend and marvellous bass player recently suggested (and I'm not sure she was joking) that I was "belligerently antiphonal violins". I don't like to think that I am belligerently anything but in musical terms I suppose this is true.

Firstly, I want to draw readers' attentions to the major British orchestra/music director combinations that currently seat their violin sections opposite one another, in what I shall hereon refer to as the 'traditional' layout:

LSO/Gergiev

LPO/Jurowski

Halle/Elder

Northern Sinfonia/Zehetmair

RSNO/Deneve

SCO/Ticciati

BBCSSO/Runnicles

LPO/Jurowski

Halle/Elder

Northern Sinfonia/Zehetmair

RSNO/Deneve

SCO/Ticciati

BBCSSO/Runnicles

and the ones that retain what I shall refer to as the 'modern' layout, ie. violins seated all together on the left:

Philharmonia/Salonen

RPO/Dutoit

CBSO/Nelsons

RLPO/Petrenko

BBCPO/Mena

BBCNOW/Fischer

RPO/Dutoit

CBSO/Nelsons

RLPO/Petrenko

BBCPO/Mena

BBCNOW/Fischer

I should add that the BBCSO under Belohlavek dabble in both layouts, depending on repertoire. This is an approach that could be considered to be thoughtful but, ultimately, unhelpful. The following notable international combinations also currently favour the 'traditional' layout:

Berliner Philharmoniker/Rattle

Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchester/Chailly

Bamberg SO/Nott

NYPO/Gilbert

Boston SO/Levine

San Francisco SO/MTT

Dresden Staatskapelle/Thielemann

Cleveland Orchestra/Welser-Most

Royal Stockholm PO/Oramo

Russian NO/Pletnev

Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchester/Chailly

Bamberg SO/Nott

NYPO/Gilbert

Boston SO/Levine

San Francisco SO/MTT

Dresden Staatskapelle/Thielemann

Cleveland Orchestra/Welser-Most

Royal Stockholm PO/Oramo

Russian NO/Pletnev

And the notable international 'modern' combinations:

Chicago SO/Muti

Philadelphia Orchestra/Nezet-Seguin

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra/Jansons

Philadelphia Orchestra/Nezet-Seguin

Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra/Jansons

These are the ones that spring foremost into my mind and there will be others, I am sure. The distribution in these lists is quite remarkable; to me, anyway. Even ten years ago the proportion of top-flight orchestras sporting the 'traditional' violin layout was small indeed (just pop the LSO, LPO, RSNO and BBCSSO into the 'modern' list and you will see what I mean just from the British perspective). I recall, when setting up my own orchestra in 2005, feeling like I was bucking the trend by opting for antiphonal violins.

|

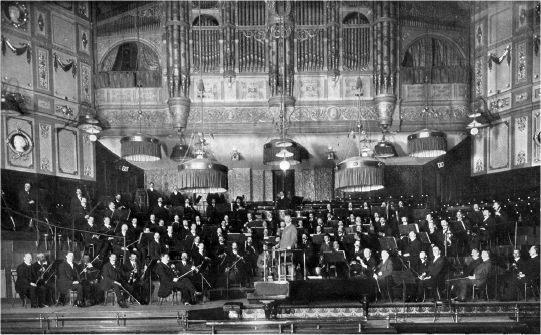

| An orchestra, probably the predecessor of the SFSO, in San Francisco, 1894 |

|

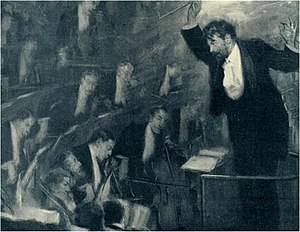

| Elgar with the LSO in 1911 |

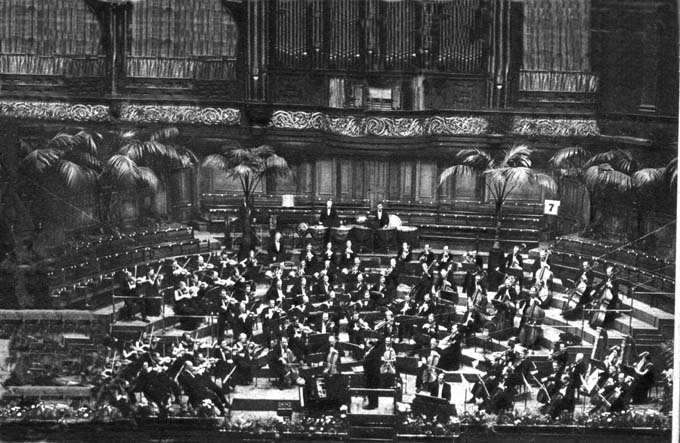

| Mahler conducting Beethoven's 9th symphony in Strasbourg, 1905 |

Why am I even bothering to write about such a triviality? The objective part of me is nagging me that the layout should not matter. It probably does not matter for the majority of concert-goers for whom the 'modern' layout seems quite normal. History tells us that there is a good reason for that. The middle of the 20th century saw a great shift from what was the 19th and early 20th century norm of antiphonal violins (see the above photographs) towards the almost uniform adoption of violins seated all together. And who should we blame/thank for this? Our very own orchestral moderniser, Sir Henry Wood.

|

| Henry Wood in 1908 as painted by Cyrus Cuneo |

Wood was responsible for many innovations in British orchestral life. He was a great supporter of female instrumentalists being taken on in orchestras and was, of course, a major figure in championing Robert Newman's Promenade concerts that are still going strong today. He also tried to do away with the practice of players deputising for his concerts which, notoriously, led to the formation of the London Symphony Orchestra in 1904. Wood was a keen innovator and was happy to experiment with various forms of orchestral layout. It is not clear whether the practice of seating the first and second violins together was his idea to begin with. Wood was a popular guest conductor both in Europe and North America and he may well have been inspired by an idea being tried in the latter continent. In any case, his New Queens Hall Orchestra (sans those truculent LSO players!) were the perfect vehicle for him to try out the new layout. Here they are pictured in the lovely Queens Hall in 1920:

|

| Sir Henry Wood conducting the New Queens Hall Orchestra in 1920 |

Wood would have soon noticed the plush string sound that could be achieved in this formation and it was not long before other conductors began to experiment with this layout for themselves. Stokowski was another famous convert. The 'Stokowski' sound of the Philadelphia Orchestra was no doubt attributed to this sort of string layout on stage. Here, however, he can be seen using the 'tradional' layout for the American premiere of Mahler's 8th symphony in 1916, clearly not yet a convert:

|

| Leopold Stokowski with the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1916 |

Other notable converts included Beecham, Bernstein, van Beinum and Karajan. That they were such giants in the middle part of the 20th century probably explains why the trend towards the 'modern' violin layout was so strong. The previous generation of conducting giants, such as Toscanini, Klemperer, Monteux, Mengelberg, Weingartner, Reiner, Mravinsky and Furtwangler continued to use the 'traditional' violin layout but it sadly all but died out with them. Unfortunately, this coincided with the development of stereo recording techniques. As such, most recordings from the stereo era (late 1950s to the present) captured the aural geography of the 'modern' layout: treble to the left and bass to the right - a most dissatisfying listening experience for me, at least, but one I largely grew up with and knew little better than.

There was, however, an apparently lone warrier: Sir Adrian Boult. He was well-known to be a most polite gentleman but his feelings on this matter were very strong indeed. You will encounter them in his books and conducting texts. His famous letter to Gramophone magazine in January 1968 documents his well-contained fury at having been forced to adopt the 'modern' violin layout for his latest recordings of the Elgar symphonies with the LPO by Lyrita Records. His argument was thus:

"I want to know whether your readers would like to hear most of their treble sound coming from the left speaker and the bass from the right or whether they want a balanced whole? With that balanced whole they will get the antiphonal effect between violins so often written for by composers from Mozart to Elgar. With the modern placing they will sometimes get a fuller sound when the firsts and seconds play in unison, but it seems to me the only advantage; while subtle effects, like Beethoven's scoring at the sixth bar of the Fifth Symphony, will come to them as from a pianoforte arrangement."

This caused quite a stir in the Gramophone correspondence columns but the overwhelming majority of readers seemed to agree with Sir Adrian. Alas, the majority of his conducting colleagues did not. Some of his acolytes kept the tradition afloat (Handley, Hickox, more recently before his untimely death, and even Sir Colin Davis on the odd occasion) but it was not for some decades that the recent trend back towards the 'traditional' layout occurred. The result for me, at least, is quite exciting. It means that many a new recording, even of core repertoire, will be only one of a handful to feature antiphonal violins captured in glorious stereo and so a great voyage of discovery lies ahead. One should not forget the great stereo recordings of Boult, Klemperer, Monteux and Reiner, of course. I was reminded of this just last night when listening to Boult conducting various London orchestras in a fine set of Wagner preludes and overtures. A future post will draw readers' attentions to some exciting new recordings featuring antiphonal violins that shed new light on familiar works.

It hardly needs saying that violins are just one aspect of the orchestral layout. With violins seated antiphonally, the cellos can be seated either to the left of centre or to the right. Some of my players refer to these layouts, respectively, as "wrong seating number one and "wrong seating number two" which, rather charmingly, illustrates just how ingrained the 'modern' seating plan is in musicians even today. Whilst I prefer the former arrangement I have been known to experiment with the latter (which may suit pieces with passages involving unison violin 1 and viola melodies particularly well). The important aspect of both of these arrangements is having the bass sound concentrated within the orchestra - a firm foundation upon which all else is built. As a conductor, one can focus this by having the celli, double basses and bassoons all in the same line of sight.

There are numerous ways to position the woodwind and brass instruments, of course, but I do not have the space to discuss these here. I would refer the curious reader to Norman Del Mar's essential 'Anatomy of the Orchestra' for further reading in this respect. It can be found at a most reasonable price from a second-hand bookseller. Del Mar has much to say on the issue of string seating and includes relevant musical examples that highlight the benefits of antiphonal violins.

If anyone asks me why I seat violins antiphonally I simply refer them to the music: the symphonies and concerti of Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, Schumann, Brahms, Mahler, Elgar and many more besides. All these benefit from the 'traditional' layout. However, I would go further than this: I assert that there are very few works that truly benefit from the 'modern' layout and so there is little reason for orchestras now to be regularly seated as such. Certainly, one can understand the reasons why the 'modern' layout was adopted at the time it was. After the first world war and beyond, the standard of major symphony orchestras was at a low ebb and the new layout probably helped to significantly develop the quality of British ensemble playing in the 20th century. Also, the new British orchestras such as the BBCSO, LPO, RPO and Philharmonia quickly became the best in their league by recruiting the best players in the interwar and post-WW2 period and so they became the standard by which other orchestras were measured, both here and abroad. It just so happened that they were conducted, mostly, by fellows who were converts to the 'modern' layout in their infancy. In the interests of balance, here is Sir Adrian caught in the act of 'trying' his mentor, Wood's layout, with his new BBCSO:

|

| The BBCSO with Sir Adrian Boult in 1930 |

The standard of modern orchestral playing is far superior to that even in the mid-20th century and so antiphonally-seated violins should pose no difficulties for today's players. Some musicians argue that 20th century composers would have been composing with the 'modern' layout in mind. I would say that this is largely untrue. Many of the more famous composers of the 20th century, such as Prokofiev, Sibelius, Strauss, Shostakovich, Stravinsky etc. would have 'grown up' with the sound of orchestras adopting the 'traditional' layout. The 'modern' layout only really became predominant from the 1950s and so it is unlikely that it would have truly influenced the writing in the majority of works from these composers. How many works would really have been written to take advantage of the violins being seated together?

There are also arguments of pragmatism thrown around. Certainly, there are pieces in which it is far more straightforward to have the violins seated together. The division of the violins in Shostakovich's 5th symphony is a classic example of this. However, this did not stop Mravinsky using the 'tradional' layout or Gergiev or Eschenbach, in this piece. It just requires more thought.

In amateur orchestras, second violin sections often feature weaker players who will either sink or swim if placed to the right of the conductor. I have found that, more often than not, such players rise to the occasion rather than lose confidence. Once these players are accustomed to the new sound world on stage they tend to adjust well. I have also found that seating them to my right increases their confidence when they would otherwise have been hidden away behind the firsts. However, a conductor would be unwise to adjust the seating upon their first visit to an orchestra. This could rapidly diminish the already fragile nascent relationship between guest conductor and orchestra. In amateur ensembles, such seating adjustment takes time unless it is instituted at their outset.

I think it will be obvious, then, to the reader that I consider the seating of violin sections together to be uncalled for in both amateur and professional circumstances. There are rare exceptions in which the conductor should consider seating them together but the uniform expectation of such a layout is merely a generational 'blip'. It is important that younger generations of musicians are educated in both the historical context and the virtues of antiphonal violins. Many well-informed colleagues and musicians still think that antiphonal violins represent some quaint 'European' style or that a certain limited period of repertoire justifies the layout on occasion. I am cheered, however, by the great musicians who have switched their allegiance over the years, even in their later years. I am thinking of Chailly, Rattle, Haitink, Gergiev and Barenboim. How I wish Mr Nelsons in Birmingham would do the same (alas, his mentor is Mariss Jansons, whose mentor was Karajan himself) and Mr Petrenko in Liverpool. This is not an argument for homogeneity between orchestras, something I bemoan often enough. Orchestras can, of course, differ in personality even if their violins are divided consistently. Maybe the best and most reasonable outcome I can hope for is a healthy mix of the two layouts.

Still, looking back at those lists at the top of the post, I can't help feeling that Sir Adrian would indeed be pleased at the way things are going.

Photographic sources: www.stokowski.org, en.wikipedia.org, www.musicalpointers.co.uk, www.nqho.com

Nelsons does sometimes seat the violins antiphonally, depending on what they are playing. As an audience member mostly prefer the "modern" layout as love to hear the cellos clearly, and have that contrast of sound, but the "traditional" layout certainly works better for some repertoire. Great blog!

ReplyDeleteThanks, I'm really pleased you like the blog! I think it is very important to get the audience perspective, which is what Sir Adrian was trying to do in his letter to Gramophone readers. Mine is very much an audience perspective also. I know what you mean about hearing the cellos speak clearly and I wonder if this is connected to the visual aspect as (the same applies to the 2nd violins) their sound should be louder, theoretically, if pointing out towards the audience from the Centre left.

ReplyDeleteDelighted to know that Andris uses antiphonal violins sometimes. I had better not now sit in my usual grand tier seat, however, as I might faint if he does when I am there!

Please keep the views coming!

Interesting Peter and, as you know, I'm with you on this issue. But...we need to consider that in the few decades where 'modern' layout was being universally applied composers were writing with that layout in mind, i.e. with a mind to creating a plush, unified violin sound as opposed to exploiting the antiphonal possibilities of the 'traditional' layout. There is also the 'third way', with violas opposite the firsts (something that Jansons adopts frequently). Again, I think it boils down to the repertoire but the effect of this third layout worked fantastically in a performance of Dvorak 8 that I saw Jansons give some years ago.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Owen. I'm still not sure that very many composers really would have incorporated the new seating plan into their ideas. I'd love to hear of any specific examples in the musical literature if anyone knows of any. Re: the 'third way' I am also quite a fan, keeping as it does the bass sound in the Centre still. You need a powerhouse viola section, though, for it to be effective I think, as Jansons would certainly have! Abbado uses this layout though I wish he would only divide his violins to go along with his other enlightened ways! I can imagine most Dvorak benefitting from violas outside placement.

ReplyDeleteAs an interesting footnote to this discussion Peter, I recently stumbled on this complete performace of Mahler 2 with the CBSO conducted by Rattle (I believe that this was his famous last performance as MD of the orchestra; for some reason never shown in full on British TV, although excerpts were broadcast as part of a documentary about Rattle's last year in charge). I had always assumed that Rattle's penchant for 'traditional' layout was a result of his work with the more old-fashioned BPO but here is evidence of him taking the same approach with the CBSO, not something that I remember from the dozens of concerts that I saw from this partership in the early-mid 1990s. Nevertheless it is a pretty fine performance!

ReplyDeletehttp://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BwRPYijLygA

Thanks Owen. Yes, I have seen bits of this performance from Brum before and been impressed. I don't think Rattle often used divided violins in Brum, though this approach can be heard on his recording of the Elgar Violin Concerto with Kennedy and in their Haydn symphony recordings. So I can only assume he had his 'epiphany' late on in his Brum career. Can anyone enlighten us further on this matter?

ReplyDeleteI have often heard the argument that the second violins on the right in the traditional setting has their F holes facing into the orchestra so their sound does not project out like the firsts. Any arrangement will put either firsts, seconds, or violas at that disadvantage. The traditional puts the seconds squarely projecting inward. The modern setting has only the violas but at least they are angled.

ReplyDeleteThe direction of the 'f' holes is certainly a practical consideration for the conductor to bear in mind but the effect is negligible in reality. The players soon adjust to any imbalance and it should be the conductor's job to sort this out. A number of factors compensate for the effect you describe. Firstly, the second violins tend to 'play up' to being on display along the front of the stage. It can boost their confidence as well, moreso in amateur settings I would imagine. Also, the visual element for the audience heightens their awareness of the second violin part. The same seems to occur when violas are placed on the outside, as is often seen.

ReplyDeleteIn recordings the microphone positioning will be crucial, too.

Finally, much of the sound from the instruments is projected upwards and so the lateral aspect becomes less important. Perhaps the composers knew best in knowing that the first violin sound would be fractionally more brilliant and louder as befits their parts.

This blog need an appreciation so I could say that this is really an awesome and worth blog! Keep writing regarding on Violin Display Case. Thanks!

ReplyDeleteYour arguments are very well put and incontestable. I have recently taken over a new orchestra and am awaiting the right time to change things! I've also heard the arguments from players about hearing each other, F holes etc. do wish me luck!

ReplyDeleteOne other conventional 'wisdom' that concerns me is the 'reducing numbers' of violins. I speak here as an arranger and orchestrator as well as a conductor (who so often asks for 'more' from the 2nds) so 14.12 etc always seems strange to me when the 1st are often stronger players and playing at a higher pitch. I recently noticed a Berlioz score in which he requests equal numbers! I rest my case.

Hi Paul - thanks very much for your comment. I wish you all the very best for the implementation of the change! I am perhaps overstating my influence but at least four amateur orchestras in the Midlands now have divided violins since I asked them to try the change. I just hope they stay that way!

ReplyDeleteI am a great admirer of Berlioz and he has left a great legacy of wisdom in his various essays. Some of his orchestration ideals are eccentric in the extreme of course! I do know what you mean about the reducing strings thing, though. Our minimum setup is 6 and 6 for the violins but I am guilty of using 8 and 6 if we have additional players although we had 7 and 7 in our last concert. I think that having slightly more players can imbue a richer sound I guess in the often higher pitched passages, which is probably the thinking behind it.

Incidentally, the latest change I made was swapping the bassoon and clarinets round so that the bassoon sit on the left, near to my double basses, thereby concentrating the bass sound further. This is based on what Del Mar suggests in his book. It is also what the Concertgebouw Orchestra do but curiously their basses sit over on the right in the annoying modern layout but I suspect this is a throwback to when they did not.

Good luck and let me know how you get on!

Great article! You might like to check this article on Psychoacoustics by Prof. Diana Deutsch, in which she gives a hypothesis about the tendency to modern layout (p. 16)

ReplyDeletehttp://wiki.dxarts.washington.edu/sandbox/groups/general/wiki/9e11b/attachments/93d1a/Psychology%20and%20Music%20-%20Diana%20Deutsch.pdf

An excellent article. I'm a fanatical listener and amateur musician, rather than a professional, and I was converted to the antiphonal violins viewpoint by Trevor Harvey writing in 'The Gramophone' in the late 1960s. In years of listening, I have come to the conclusion that there is no real disadvantage - ever - to using the traditional layout, as long as there are equal numbers of firsts and seconds. If the violas are placed on the left of centre (as for example Monteux used), this is very successful with a lot of music (there are many occasions where composers write for the first violins and violas in octaves), for example Haydn and Beethoven. (Though an independent viola line always seems a bit less prominent when they are here.) Mozart and Mendelssohn, on the other hand, often write a counter-melody in octaves for seconds and violas, and this sounds best when both are on the right, with the 'cellos on the left. The interest in authentic performances has meant that some conductors seem to have chosen the proper layout for historic rather than musical reasons, but at least you get to hear the music as it should sound. Unfortunately, it means that later composers such as Tchaikovsky rarely get the correct layout: the trio of the String Serenade's Waltz, as played by the LPO under Norman del Mar, makes all other performances seem one-dimensional. The middle section of Francesca da Rimini under Pletnev is another magical experience. Sibelius is another composer who has rarely been played as he should.

ReplyDeleteIncidentally, another of my interests is Second World War propaganda films. I have seen several of these where the orchestras, both professional and less so, are arranged with divided violins. There's also the 1948 film 'Unfaithfully Yours', showing Rex Harrison rehearsing and conducting an orchestra arranged the same way.

Great and I have a super provide: What Was The First Home Renovation Show cost to gut renovate a house

ReplyDelete